— Please, tell us a bit about yourself. What was your start in the industry, where you studied, and what are your duties in the company?

— I have graduated from the Physics and Mathematics Department of the Peoples’ Friendship University of Russia. Long ago, in the year 1994, my friends and I created a design studio, mostly focused on printing. Step by step, it became a basis for an advertising agency, and our range of services increased. We did printing, made souvenirs, and arranged corporate events. It was like any other small advertising agency in Russia. At some point, the need arose for 3D, 3D Max models, and stuff like that. So we hired people who deal with it and over time, a whole department was created. The United 3D Labs independent laboratory for computer graphics later separated from this department. In 2008, I left the agency and transferred to this company. Since then we have been doing this.

— What projects is the company currently managing and how many people are involved in them?

— We have a team of 20 people working on the projects. Those are widely different projects, which is quite a rare thing for the Russian computer graphics market. We do both works based on the traditional pre-rendered works, such as commercials and presentation videos, and modern interactive projects with real-time rendering: mappings, installations, and museum expositions. This is our area of activity. We think we deal with almost everything except traditional TV and cinema. We focus on content, its playback and presentation, so we try not to tamper with the hardware too much. However, we will tinker and fasten anything if we need to. First of all, it has to look good, be catchy and unconventional. Our company is one of the few, if not the only one, to actually have pipeline with images over 10K resolution. We do not just make relatively simple motion graphics. We can do photorealistic graphics and animation with a resolution like that Few companies can do that.

— How did you manage this pipeline?

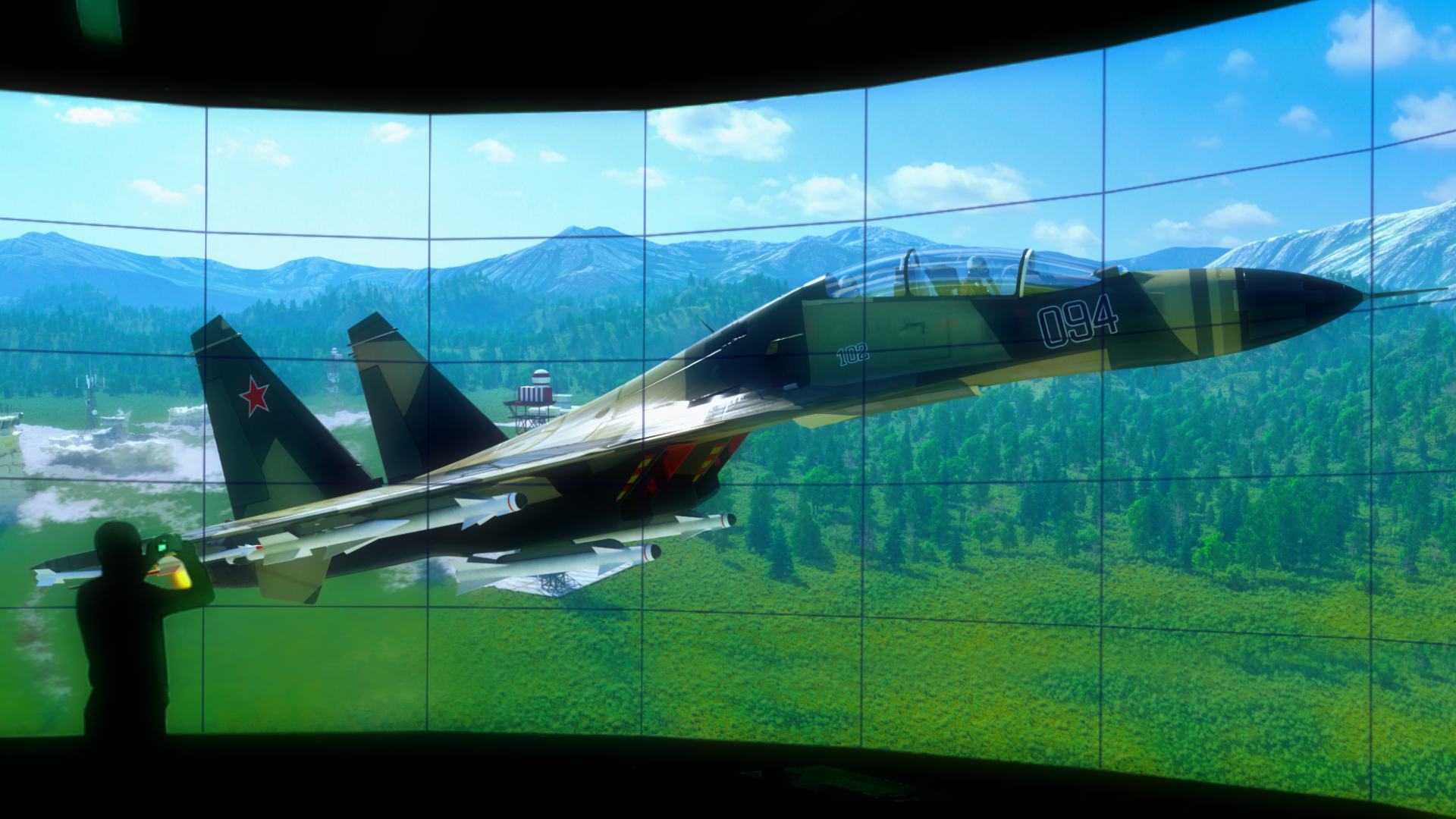

— It’s just one of our focus areas. One of our customers required such high-resolution images. A major Russian industrial enterprise has a showroom, where they need to display real-time graphics. They use Ventuz for that; the process is controlled by a computer cluster. A huge wall of 80 full HD displays is constantly screening clips about the products and capabilities of the enterprise. Those clips were the reason why we needed the pipeline to work with this resolution. There is a GPU render farm; our entire local network uses InfiniBand with 56 Gb/s of speed instead of common Ethernet; 512 GB RAM workstations. Of course, anything can render these resolutions, it’s not a problem. The problem is that we have to do a project in a month, not in 10 years. This is our unique area of activity, and the company’s main advantage is that we deal with really complicated high-tech tasks, while making them nice to look at. You know, some people like unconventional solutions—using tracking or something—that have no beauty to them. We are trying to consider the aesthetics as well. Lately, we have been largely engaged in virtual and augmented reality projects.

— Since we are talking about beauty, tell us about your most impressive projects for customers, viewers. What methods can be used to achieve it?

— It’s not easy to please everyone. Different people like different things. It is like the old story about the Black Square by Malevich, when some people say it is garbage, and others think it is a great masterpiece of art. We work for the sake of our viewers, so we avoid obscure abstraction which only our colleagues can appreciate. Perhaps it is worth mentioning one of our latest works, completed in Kazan in January. It was a city panorama, a four-storey museum full of installations (a total of 17). There were things to suit any taste; we tried to satisfy everyone. We started thinking of what will be there during the concept development phase—it is very rare for developers to get involved at such an early stage. Many thanks to the customer, who gave us the opportunity to implement this project. We were developing all the components together with scholars from the Institute of Archeology under the Tatarstan Academy of Sciences. They were telling us what installations should be demonstrating from a scientific point of view, while we were trying to make it work. The museum is a city panorama, it tells people about Kazan, its past and present. It is a conventional museum of city history, but it is also very modern: it focuses both on education and entertainment. We tried to make the entertaining part interesting for everyone: augmented and virtual reality, children’s games, traditional presentations, a historical timeline. Everything that makes getting acquainted with the city history as exciting as possible. We wanted to please everyone—that is, if someone dislikes one thing, they should like another. Considering the reviews, we have succeeded. Kazan actually has few such museums; even Moscow cannot boast many of them. So our project made quite a splash, partially because it wasn’t just one unique and beautiful solution, but several various solutions, hitting the same goal.

— What projects made you the most confident, as in “there is nothing to change, everything hits the right spot”?

— I don’t really think such projects exist, because now, as some time have passed, we would make a lot of changes even in the Kazan city panorama we’ve just mentioned. All installations have a common control system, and we can see in real time, which of them are popular or not, and whether some concepts are implemented at the exhibitions or not. We see how people interact with all of this. And we would definitely refashion some parts completely. So there are no projects where you don’t want to change anything. However, sometimes you only want minor changes. Rock opera Crime and Punishment, staged at the Moscow Musical Theatre and directed by Konchalovsky, is one of such projects. All its visualization was made by us; it was the first time when projection mapping was done on moving scenery in a Russian theatre. There is a tracking system, all the scenery has markers, cameras are working, and projection devices display images in real time. It’s not exactly easy to work with Andrei Konchalovsky. Many things were confusing at first, but the play has been on for a year now, and we understand that the master was right. This is the case when you first want to fix something, but then you look again and realize that leaving everything intact was a good idea. But in general, any work wants improvement to some extent.

— As for corrections, have you faced any problems in projects and how did you solve them?

— As for corrections, have you faced any problems in projects and how did you solve them?

— If it’s not a plain video made at the office, checked ten times, reviewed in the demo room, and then handed to the customer, but a complex installation for museum or exhibition, then of course, we face a lot of problems. First of all, this is due to the fact that there is never enough time for testing. Everyone trashes Microsoft for constant bug-fixing, but we need to understand what an intense job it is and how much time it takes for the tester. Microsoft can afford it, but we rarely have such an opportunity; everything is done basically on the fly. Something is corrected on the ground, something is done at the office, then we send it again.

I have to point out that we, like many other companies in the industry, use a wide range of software and hardware, which, in fact, is absolutely not designed for our activities. Game engines like Unity and Unreal are used for complex exhibitions simply because we do not have anything more suitable. Or, for example, Ventuz, which is used as a plain video display system because all the other ways to do it are even more difficult and cost considerable money. Anyway, we somehow adapt everything to our needs. Naturally, problems do arise at times. We try to solve them quickly, sometimes with a hammer. Common videos and pre-rendered works rarely present any difficulty, and in most cases they can be changed, fixed later and cut again. Museum exhibitions are basically the same. But when a museum installation is on, then Putin, Medvedev, and others come the next day—that’s where all the fun begins. Sometimes we do all-nighters and fix everything, but we generally try to avoid it, unlike many colleagues. We are of a strong opinion that programmers should not code at night. A code written at night needs to be completely re-written the next morning. We try to stick to this principle.

— You mean, you do have deadlines, but you also try to support employees?

— We do have very tight deadlines. For example, our activities partially overlap with game development. No one will even be surprised if a new game is released a month later; this is common for them. As for us, if the exhibition opens the next day and important people are expected to come, everything must work like a charm. On the other hand, we try to arrange the whole process so that we have as few failures as possible. Thus, the pace is comfortable: if you need it tomorrow, it will be ready tomorrow. No need to work until four in the morning to get it done.

— Excellent approach. Now tell us about your work with Cerebro. How long have you used it and how did it assimilate in the company?

— In fact, Cerebro helps us keep going with this approach. Take the Kazan panorama: there are 17 installations, each of them is divided into N tasks, a total of some two hundred. Obviously, you need a seamless system to manage and control these tasks; otherwise it will be very hard to stick to a comfortable schedule. Therefore, Cerebro has naturalized among us just fine, because we always try to work according to the plan. When you have one or two tasks—to make a show or an exhibition—then, of course, you can all get together, gang up on it and do everything really fast. But if you constantly live at this pace, it gets very rough. People start to leave, and you realize: you cannot live like this. In this respect, Cerebro is an indispensable tool that helps with the overload of small tasks. It is an absolutely brilliant thing.

We have come to Cerebro step by step. In our work, we have a methodical approach to everything: first we studied foreign systems, for example, Shotgun, which we used for a couple of months and thought it was inconvenient. Then we tried Russian control systems, say, Bitrix24, and came to the same conclusion. Thus, we started working with Cerebro and suddenly realized that it was convenient, even though the introduction process did not escape complications. Implementation of any control system in the team is a difficult task for everyone. After all, it is much easier for a designer to explain things in a conversation, or maybe in an email, but here you need to register and manage something, and they do not like it. Novelties are always painful, but we mastered it in some three months. We have been working with Cerebro for about two years, and it no longer raises any questions; everything is calm. New employees quickly master its basics. Once it is installed for the first time, it is easier to keep working. Cerebro is an extremely useful and convenient tool to simultaneously manage a large number of orders, broken down into small subtasks. This is largely due to the fact that the program was written by people who understand our industry. It is especially striking in the details. As for the other systems… We have tested them and realized that they do not suit us. Strangely enough, even the globally known Shotgun. I, as someone who has tried both systems, can objectively admit that this solution is less convenient than Cerebro.

— Thank you for your honest answer. Could you tell us which features of Cerebro you use regularly and which ones you do not use at all?

— Thank you for your honest answer. Could you tell us which features of Cerebro you use regularly and which ones you do not use at all?

— In fact, we barely use one-third of all features that Cerebro provides. If we talk about what is constantly used for work, then, first of all, it is the list of tasks with the entire tree of subtasks and a forum for messages on each task. And, of course, a brilliant invention of Mirada. Everything else is used to a lesser extent. In my opinion, Cerebro has a somewhat overwhelming interface. It is as if the developers tried to fit everything in, so the UI we see now is quite complex. On the other hand, this is a trifling thing, you can just ignore it. Since we do not have piecework and do not involve freelance vendors, we don’t get to use the time-tracking functions and all the Gantt chart-related features. Again, our company is not very big. I understand that time tracking and control is needed for piecework or a large organization. But at this stage, we have other problems at hand. But as for order management, the opportunity to see all previews at once and leave comments is very convenient. With our systematic approach, we are happy that everything is in one place. You know the common routine: email, corporate chat, personal communication… As a result, no one understands who said what and to whom, as well as when and what to do. Especially if the manager said one thing and the art director said another. Now that this is all strictly within Cerebro, even if there are issues, they are promptly solved, we just have to view the task history. It helps a lot with our work.

— What else besides the interface you dislike in our product? What would you like us to improve?

— I wouldn’t say I find the existing interface unacceptable. Yes, I do think it is somewhat overloaded, but it’s the matter of taste. Someone likes to drive a BMW, someone prefers Toyota. In fact, everything works very well.

Up to 50 users

50 GB cloud storage space

Unlimited number of tasks

No credit card required

— I have graduated from the Physics and Mathematics Department of the Peoples’ Friendship University of Russia. Long ago, in the year 1994, my friends and I created a design studio, mostly focused on printing. Step by step, it became a basis for an advertising agency, and our range of services increased. We did printing, made souvenirs, and arranged corporate events. It was like any other small advertising agency in Russia. At some point, the need arose for 3D, 3D Max models, and stuff like that. So we hired people who deal with it and over time, a whole department was created. The United 3D Labs independent laboratory for computer graphics later separated from this department. In 2008, I left the agency and transferred to this company. Since then we have been doing this.

— What projects is the company currently managing and how many people are involved in them?

— We have a team of 20 people working on the projects. Those are widely different projects, which is quite a rare thing for the Russian computer graphics market. We do both works based on the traditional pre-rendered works, such as commercials and presentation videos, and modern interactive projects with real-time rendering: mappings, installations, and museum expositions. This is our area of activity. We think we deal with almost everything except traditional TV and cinema. We focus on content, its playback and presentation, so we try not to tamper with the hardware too much. However, we will tinker and fasten anything if we need to. First of all, it has to look good, be catchy and unconventional. Our company is one of the few, if not the only one, to actually have pipeline with images over 10K resolution. We do not just make relatively simple motion graphics. We can do photorealistic graphics and animation with a resolution like that Few companies can do that.

— How did you manage this pipeline?

— It’s just one of our focus areas. One of our customers required such high-resolution images. A major Russian industrial enterprise has a showroom, where they need to display real-time graphics. They use Ventuz for that; the process is controlled by a computer cluster. A huge wall of 80 full HD displays is constantly screening clips about the products and capabilities of the enterprise. Those clips were the reason why we needed the pipeline to work with this resolution. There is a GPU render farm; our entire local network uses InfiniBand with 56 Gb/s of speed instead of common Ethernet; 512 GB RAM workstations. Of course, anything can render these resolutions, it’s not a problem. The problem is that we have to do a project in a month, not in 10 years. This is our unique area of activity, and the company’s main advantage is that we deal with really complicated high-tech tasks, while making them nice to look at. You know, some people like unconventional solutions—using tracking or something—that have no beauty to them. We are trying to consider the aesthetics as well. Lately, we have been largely engaged in virtual and augmented reality projects.

— Since we are talking about beauty, tell us about your most impressive projects for customers, viewers. What methods can be used to achieve it?

— It’s not easy to please everyone. Different people like different things. It is like the old story about the Black Square by Malevich, when some people say it is garbage, and others think it is a great masterpiece of art. We work for the sake of our viewers, so we avoid obscure abstraction which only our colleagues can appreciate. Perhaps it is worth mentioning one of our latest works, completed in Kazan in January. It was a city panorama, a four-storey museum full of installations (a total of 17). There were things to suit any taste; we tried to satisfy everyone. We started thinking of what will be there during the concept development phase—it is very rare for developers to get involved at such an early stage. Many thanks to the customer, who gave us the opportunity to implement this project. We were developing all the components together with scholars from the Institute of Archeology under the Tatarstan Academy of Sciences. They were telling us what installations should be demonstrating from a scientific point of view, while we were trying to make it work. The museum is a city panorama, it tells people about Kazan, its past and present. It is a conventional museum of city history, but it is also very modern: it focuses both on education and entertainment. We tried to make the entertaining part interesting for everyone: augmented and virtual reality, children’s games, traditional presentations, a historical timeline. Everything that makes getting acquainted with the city history as exciting as possible. We wanted to please everyone—that is, if someone dislikes one thing, they should like another. Considering the reviews, we have succeeded. Kazan actually has few such museums; even Moscow cannot boast many of them. So our project made quite a splash, partially because it wasn’t just one unique and beautiful solution, but several various solutions, hitting the same goal.

— What projects made you the most confident, as in “there is nothing to change, everything hits the right spot”?

— I don’t really think such projects exist, because now, as some time have passed, we would make a lot of changes even in the Kazan city panorama we’ve just mentioned. All installations have a common control system, and we can see in real time, which of them are popular or not, and whether some concepts are implemented at the exhibitions or not. We see how people interact with all of this. And we would definitely refashion some parts completely. So there are no projects where you don’t want to change anything. However, sometimes you only want minor changes. Rock opera Crime and Punishment, staged at the Moscow Musical Theatre and directed by Konchalovsky, is one of such projects. All its visualization was made by us; it was the first time when projection mapping was done on moving scenery in a Russian theatre. There is a tracking system, all the scenery has markers, cameras are working, and projection devices display images in real time. It’s not exactly easy to work with Andrei Konchalovsky. Many things were confusing at first, but the play has been on for a year now, and we understand that the master was right. This is the case when you first want to fix something, but then you look again and realize that leaving everything intact was a good idea. But in general, any work wants improvement to some extent.

— I have graduated from the Physics and Mathematics Department of the Peoples’ Friendship University of Russia. Long ago, in the year 1994, my friends and I created a design studio, mostly focused on printing. Step by step, it became a basis for an advertising agency, and our range of services increased. We did printing, made souvenirs, and arranged corporate events. It was like any other small advertising agency in Russia. At some point, the need arose for 3D, 3D Max models, and stuff like that. So we hired people who deal with it and over time, a whole department was created. The United 3D Labs independent laboratory for computer graphics later separated from this department. In 2008, I left the agency and transferred to this company. Since then we have been doing this.

— What projects is the company currently managing and how many people are involved in them?

— We have a team of 20 people working on the projects. Those are widely different projects, which is quite a rare thing for the Russian computer graphics market. We do both works based on the traditional pre-rendered works, such as commercials and presentation videos, and modern interactive projects with real-time rendering: mappings, installations, and museum expositions. This is our area of activity. We think we deal with almost everything except traditional TV and cinema. We focus on content, its playback and presentation, so we try not to tamper with the hardware too much. However, we will tinker and fasten anything if we need to. First of all, it has to look good, be catchy and unconventional. Our company is one of the few, if not the only one, to actually have pipeline with images over 10K resolution. We do not just make relatively simple motion graphics. We can do photorealistic graphics and animation with a resolution like that Few companies can do that.

— How did you manage this pipeline?

— It’s just one of our focus areas. One of our customers required such high-resolution images. A major Russian industrial enterprise has a showroom, where they need to display real-time graphics. They use Ventuz for that; the process is controlled by a computer cluster. A huge wall of 80 full HD displays is constantly screening clips about the products and capabilities of the enterprise. Those clips were the reason why we needed the pipeline to work with this resolution. There is a GPU render farm; our entire local network uses InfiniBand with 56 Gb/s of speed instead of common Ethernet; 512 GB RAM workstations. Of course, anything can render these resolutions, it’s not a problem. The problem is that we have to do a project in a month, not in 10 years. This is our unique area of activity, and the company’s main advantage is that we deal with really complicated high-tech tasks, while making them nice to look at. You know, some people like unconventional solutions—using tracking or something—that have no beauty to them. We are trying to consider the aesthetics as well. Lately, we have been largely engaged in virtual and augmented reality projects.

— Since we are talking about beauty, tell us about your most impressive projects for customers, viewers. What methods can be used to achieve it?

— It’s not easy to please everyone. Different people like different things. It is like the old story about the Black Square by Malevich, when some people say it is garbage, and others think it is a great masterpiece of art. We work for the sake of our viewers, so we avoid obscure abstraction which only our colleagues can appreciate. Perhaps it is worth mentioning one of our latest works, completed in Kazan in January. It was a city panorama, a four-storey museum full of installations (a total of 17). There were things to suit any taste; we tried to satisfy everyone. We started thinking of what will be there during the concept development phase—it is very rare for developers to get involved at such an early stage. Many thanks to the customer, who gave us the opportunity to implement this project. We were developing all the components together with scholars from the Institute of Archeology under the Tatarstan Academy of Sciences. They were telling us what installations should be demonstrating from a scientific point of view, while we were trying to make it work. The museum is a city panorama, it tells people about Kazan, its past and present. It is a conventional museum of city history, but it is also very modern: it focuses both on education and entertainment. We tried to make the entertaining part interesting for everyone: augmented and virtual reality, children’s games, traditional presentations, a historical timeline. Everything that makes getting acquainted with the city history as exciting as possible. We wanted to please everyone—that is, if someone dislikes one thing, they should like another. Considering the reviews, we have succeeded. Kazan actually has few such museums; even Moscow cannot boast many of them. So our project made quite a splash, partially because it wasn’t just one unique and beautiful solution, but several various solutions, hitting the same goal.

— What projects made you the most confident, as in “there is nothing to change, everything hits the right spot”?

— I don’t really think such projects exist, because now, as some time have passed, we would make a lot of changes even in the Kazan city panorama we’ve just mentioned. All installations have a common control system, and we can see in real time, which of them are popular or not, and whether some concepts are implemented at the exhibitions or not. We see how people interact with all of this. And we would definitely refashion some parts completely. So there are no projects where you don’t want to change anything. However, sometimes you only want minor changes. Rock opera Crime and Punishment, staged at the Moscow Musical Theatre and directed by Konchalovsky, is one of such projects. All its visualization was made by us; it was the first time when projection mapping was done on moving scenery in a Russian theatre. There is a tracking system, all the scenery has markers, cameras are working, and projection devices display images in real time. It’s not exactly easy to work with Andrei Konchalovsky. Many things were confusing at first, but the play has been on for a year now, and we understand that the master was right. This is the case when you first want to fix something, but then you look again and realize that leaving everything intact was a good idea. But in general, any work wants improvement to some extent.

— As for corrections, have you faced any problems in projects and how did you solve them?

— If it’s not a plain video made at the office, checked ten times, reviewed in the demo room, and then handed to the customer, but a complex installation for museum or exhibition, then of course, we face a lot of problems. First of all, this is due to the fact that there is never enough time for testing. Everyone trashes Microsoft for constant bug-fixing, but we need to understand what an intense job it is and how much time it takes for the tester. Microsoft can afford it, but we rarely have such an opportunity; everything is done basically on the fly. Something is corrected on the ground, something is done at the office, then we send it again.

I have to point out that we, like many other companies in the industry, use a wide range of software and hardware, which, in fact, is absolutely not designed for our activities. Game engines like Unity and Unreal are used for complex exhibitions simply because we do not have anything more suitable. Or, for example, Ventuz, which is used as a plain video display system because all the other ways to do it are even more difficult and cost considerable money. Anyway, we somehow adapt everything to our needs. Naturally, problems do arise at times. We try to solve them quickly, sometimes with a hammer. Common videos and pre-rendered works rarely present any difficulty, and in most cases they can be changed, fixed later and cut again. Museum exhibitions are basically the same. But when a museum installation is on, then Putin, Medvedev, and others come the next day—that’s where all the fun begins. Sometimes we do all-nighters and fix everything, but we generally try to avoid it, unlike many colleagues. We are of a strong opinion that programmers should not code at night. A code written at night needs to be completely re-written the next morning. We try to stick to this principle.

— You mean, you do have deadlines, but you also try to support employees?

— We do have very tight deadlines. For example, our activities partially overlap with game development. No one will even be surprised if a new game is released a month later; this is common for them. As for us, if the exhibition opens the next day and important people are expected to come, everything must work like a charm. On the other hand, we try to arrange the whole process so that we have as few failures as possible. Thus, the pace is comfortable: if you need it tomorrow, it will be ready tomorrow. No need to work until four in the morning to get it done.

— Excellent approach. Now tell us about your work with Cerebro. How long have you used it and how did it assimilate in the company?

— In fact, Cerebro helps us keep going with this approach. Take the Kazan panorama: there are 17 installations, each of them is divided into N tasks, a total of some two hundred. Obviously, you need a seamless system to manage and control these tasks; otherwise it will be very hard to stick to a comfortable schedule. Therefore, Cerebro has naturalized among us just fine, because we always try to work according to the plan. When you have one or two tasks—to make a show or an exhibition—then, of course, you can all get together, gang up on it and do everything really fast. But if you constantly live at this pace, it gets very rough. People start to leave, and you realize: you cannot live like this. In this respect, Cerebro is an indispensable tool that helps with the overload of small tasks. It is an absolutely brilliant thing.

We have come to Cerebro step by step. In our work, we have a methodical approach to everything: first we studied foreign systems, for example, Shotgun, which we used for a couple of months and thought it was inconvenient. Then we tried Russian control systems, say, Bitrix24, and came to the same conclusion. Thus, we started working with Cerebro and suddenly realized that it was convenient, even though the introduction process did not escape complications. Implementation of any control system in the team is a difficult task for everyone. After all, it is much easier for a designer to explain things in a conversation, or maybe in an email, but here you need to register and manage something, and they do not like it. Novelties are always painful, but we mastered it in some three months. We have been working with Cerebro for about two years, and it no longer raises any questions; everything is calm. New employees quickly master its basics. Once it is installed for the first time, it is easier to keep working. Cerebro is an extremely useful and convenient tool to simultaneously manage a large number of orders, broken down into small subtasks. This is largely due to the fact that the program was written by people who understand our industry. It is especially striking in the details. As for the other systems… We have tested them and realized that they do not suit us. Strangely enough, even the globally known Shotgun. I, as someone who has tried both systems, can objectively admit that this solution is less convenient than Cerebro.

— As for corrections, have you faced any problems in projects and how did you solve them?

— If it’s not a plain video made at the office, checked ten times, reviewed in the demo room, and then handed to the customer, but a complex installation for museum or exhibition, then of course, we face a lot of problems. First of all, this is due to the fact that there is never enough time for testing. Everyone trashes Microsoft for constant bug-fixing, but we need to understand what an intense job it is and how much time it takes for the tester. Microsoft can afford it, but we rarely have such an opportunity; everything is done basically on the fly. Something is corrected on the ground, something is done at the office, then we send it again.

I have to point out that we, like many other companies in the industry, use a wide range of software and hardware, which, in fact, is absolutely not designed for our activities. Game engines like Unity and Unreal are used for complex exhibitions simply because we do not have anything more suitable. Or, for example, Ventuz, which is used as a plain video display system because all the other ways to do it are even more difficult and cost considerable money. Anyway, we somehow adapt everything to our needs. Naturally, problems do arise at times. We try to solve them quickly, sometimes with a hammer. Common videos and pre-rendered works rarely present any difficulty, and in most cases they can be changed, fixed later and cut again. Museum exhibitions are basically the same. But when a museum installation is on, then Putin, Medvedev, and others come the next day—that’s where all the fun begins. Sometimes we do all-nighters and fix everything, but we generally try to avoid it, unlike many colleagues. We are of a strong opinion that programmers should not code at night. A code written at night needs to be completely re-written the next morning. We try to stick to this principle.

— You mean, you do have deadlines, but you also try to support employees?

— We do have very tight deadlines. For example, our activities partially overlap with game development. No one will even be surprised if a new game is released a month later; this is common for them. As for us, if the exhibition opens the next day and important people are expected to come, everything must work like a charm. On the other hand, we try to arrange the whole process so that we have as few failures as possible. Thus, the pace is comfortable: if you need it tomorrow, it will be ready tomorrow. No need to work until four in the morning to get it done.

— Excellent approach. Now tell us about your work with Cerebro. How long have you used it and how did it assimilate in the company?

— In fact, Cerebro helps us keep going with this approach. Take the Kazan panorama: there are 17 installations, each of them is divided into N tasks, a total of some two hundred. Obviously, you need a seamless system to manage and control these tasks; otherwise it will be very hard to stick to a comfortable schedule. Therefore, Cerebro has naturalized among us just fine, because we always try to work according to the plan. When you have one or two tasks—to make a show or an exhibition—then, of course, you can all get together, gang up on it and do everything really fast. But if you constantly live at this pace, it gets very rough. People start to leave, and you realize: you cannot live like this. In this respect, Cerebro is an indispensable tool that helps with the overload of small tasks. It is an absolutely brilliant thing.

We have come to Cerebro step by step. In our work, we have a methodical approach to everything: first we studied foreign systems, for example, Shotgun, which we used for a couple of months and thought it was inconvenient. Then we tried Russian control systems, say, Bitrix24, and came to the same conclusion. Thus, we started working with Cerebro and suddenly realized that it was convenient, even though the introduction process did not escape complications. Implementation of any control system in the team is a difficult task for everyone. After all, it is much easier for a designer to explain things in a conversation, or maybe in an email, but here you need to register and manage something, and they do not like it. Novelties are always painful, but we mastered it in some three months. We have been working with Cerebro for about two years, and it no longer raises any questions; everything is calm. New employees quickly master its basics. Once it is installed for the first time, it is easier to keep working. Cerebro is an extremely useful and convenient tool to simultaneously manage a large number of orders, broken down into small subtasks. This is largely due to the fact that the program was written by people who understand our industry. It is especially striking in the details. As for the other systems… We have tested them and realized that they do not suit us. Strangely enough, even the globally known Shotgun. I, as someone who has tried both systems, can objectively admit that this solution is less convenient than Cerebro.

— Thank you for your honest answer. Could you tell us which features of Cerebro you use regularly and which ones you do not use at all?

— In fact, we barely use one-third of all features that Cerebro provides. If we talk about what is constantly used for work, then, first of all, it is the list of tasks with the entire tree of subtasks and a forum for messages on each task. And, of course, a brilliant invention of Mirada. Everything else is used to a lesser extent. In my opinion, Cerebro has a somewhat overwhelming interface. It is as if the developers tried to fit everything in, so the UI we see now is quite complex. On the other hand, this is a trifling thing, you can just ignore it. Since we do not have piecework and do not involve freelance vendors, we don’t get to use the time-tracking functions and all the Gantt chart-related features. Again, our company is not very big. I understand that time tracking and control is needed for piecework or a large organization. But at this stage, we have other problems at hand. But as for order management, the opportunity to see all previews at once and leave comments is very convenient. With our systematic approach, we are happy that everything is in one place. You know the common routine: email, corporate chat, personal communication… As a result, no one understands who said what and to whom, as well as when and what to do. Especially if the manager said one thing and the art director said another. Now that this is all strictly within Cerebro, even if there are issues, they are promptly solved, we just have to view the task history. It helps a lot with our work.

— What else besides the interface you dislike in our product? What would you like us to improve?

— I wouldn’t say I find the existing interface unacceptable. Yes, I do think it is somewhat overloaded, but it’s the matter of taste. Someone likes to drive a BMW, someone prefers Toyota. In fact, everything works very well.

— Thank you for your honest answer. Could you tell us which features of Cerebro you use regularly and which ones you do not use at all?

— In fact, we barely use one-third of all features that Cerebro provides. If we talk about what is constantly used for work, then, first of all, it is the list of tasks with the entire tree of subtasks and a forum for messages on each task. And, of course, a brilliant invention of Mirada. Everything else is used to a lesser extent. In my opinion, Cerebro has a somewhat overwhelming interface. It is as if the developers tried to fit everything in, so the UI we see now is quite complex. On the other hand, this is a trifling thing, you can just ignore it. Since we do not have piecework and do not involve freelance vendors, we don’t get to use the time-tracking functions and all the Gantt chart-related features. Again, our company is not very big. I understand that time tracking and control is needed for piecework or a large organization. But at this stage, we have other problems at hand. But as for order management, the opportunity to see all previews at once and leave comments is very convenient. With our systematic approach, we are happy that everything is in one place. You know the common routine: email, corporate chat, personal communication… As a result, no one understands who said what and to whom, as well as when and what to do. Especially if the manager said one thing and the art director said another. Now that this is all strictly within Cerebro, even if there are issues, they are promptly solved, we just have to view the task history. It helps a lot with our work.

— What else besides the interface you dislike in our product? What would you like us to improve?

— I wouldn’t say I find the existing interface unacceptable. Yes, I do think it is somewhat overloaded, but it’s the matter of taste. Someone likes to drive a BMW, someone prefers Toyota. In fact, everything works very well.